I believe that drafting (drawing) is the most feared component of representational painting. It parallels the fear of math in our educational system. Or the fear of scales in music training. It is a demanding mistress. One reason for the fear is that drafting is the thing most often noticed by the layman when it is lacking.

Because the fear of drafting is prevalent in the art community, then portrait painting is seen as the hardest of the genres of representational painting. And landscape painting is seen as one of the easiest. I had a teacher explain to me once that if a nose is a quarter inch off in a portrait, it is immediately evident, but if a branch on a tree is a quarter inch off, then that isn’t a big deal.

There is some truth to this, but the broad generality that landscape painting is easy is false. And here is why.

REASON 1: COMPOSITION

Composition is a significant component of all art and design. Making sure that there is a clear center of interest and that the rest of the artwork is subordinate to that center of interest is important. This is sometimes referred to as “orchestration.”

Choosing a center of interest in portraiture is simple. The center of interest is the face. As humans, we immediately gravitate to a person’s face.

This painting by John Singer Sargent is a good example.

Lady Agnew by John Singer Sargent

The same goes for figure painting – the face will generally be the center of interest.

A Silent Walk - Jeremy Lipking

You will notice that in the painting by Jeremy Winborg below, there is a lot going on. But even so, the face is still the center of interest.

Jeremy Winborg - Unknown Title

Ditto for the painting of wildlife.

The Great Bear by Bob Kuhn

In still life painting, the still life is arranged by the painter who chooses the composition before even beginning to work, but you can’t arrange the landscape to meet your compositional needs. Or can you? More later.

In this still life painting, one area is easily seen as the center of interest - the orange slices, grape, and reflection on the copper pot.

Jerry Weers - Unknown Title

One way to overcome the issue of determining the center of interest in a landscape is to add some human figures. Those figures immediately draw the viewer’s attention and can become the center of interest of the painting. Add some human figures and the problem is apparently solved.

Edgar Payne - Unknown Title

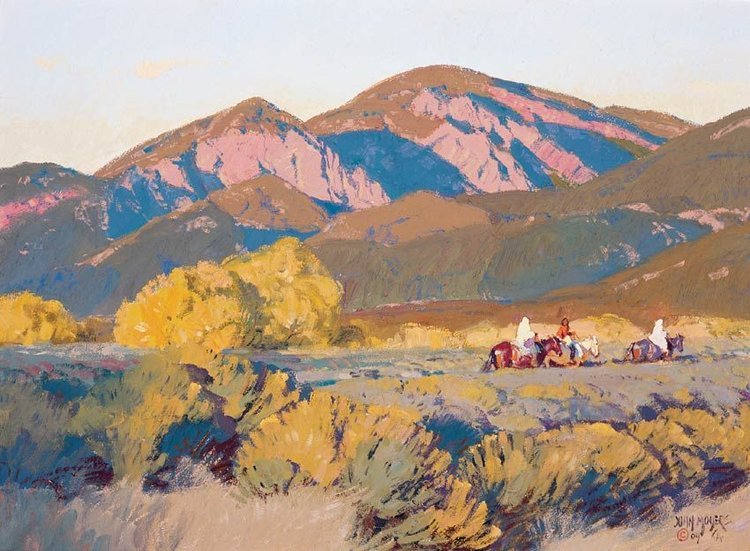

Taos Sun - John Moyers

Of course, this is not quite as easy as it seems. A center of interest is most often the place in a painting that has the most contrast (brightest lights and darkest darks), the most intense colors, and the highest detail. So, you could have a landscape painting in which a patch of light on a cliff is the most vibrant spot and the figures are a distraction, unless the figures are purposefully made less vibrant or detailed. So, orchestration of the composition must still take place when adding figures to a landscape. .

In this Edgar Payne landscape painting, the figures do not draw the eye but are added simply to show the immensity of the landscape around them. The true center of interest is the light and shadow on the cliffs. Notice how the row of horses draws your eyes back towards the cliffs.

Edgar Payne - Unknown Title

In this painting by G. Russell Case, the figures are the center of interest.

G. Russell Case - Unknown Title

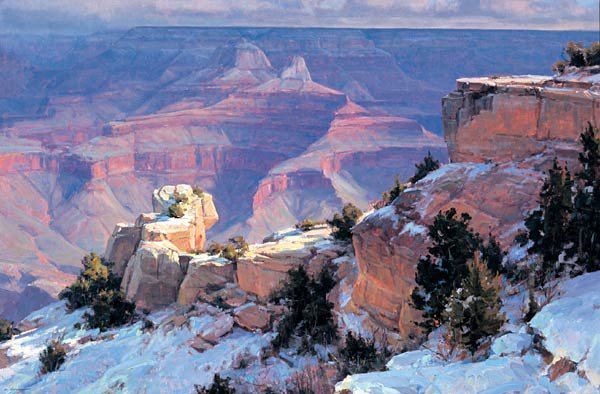

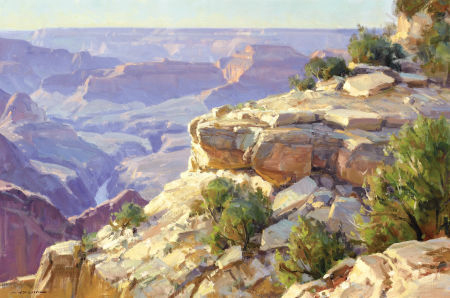

Pure landscape (without humans) is difficult because you must figure out a center of interest and then subordinate everything else to it. This is tough because when you look at the landscape around you, you see many things that are beautiful. Think of an iconic landscape like the Grand Canyon. If you are at the rim looking into the Grand Canyon at sunset or sunrise, you can see some spots of beautiful light, perhaps an interesting, gnarled tree growing on the rim, and some fantastic cloud formations in the distance. And if you were to paint the scene, it is tempting to add all of the beautiful things you notice to the painting. However, if you do that, then the viewer’s eye jumps from one pretty thing to the next, and the feeling of the painting is somewhat unsettling.

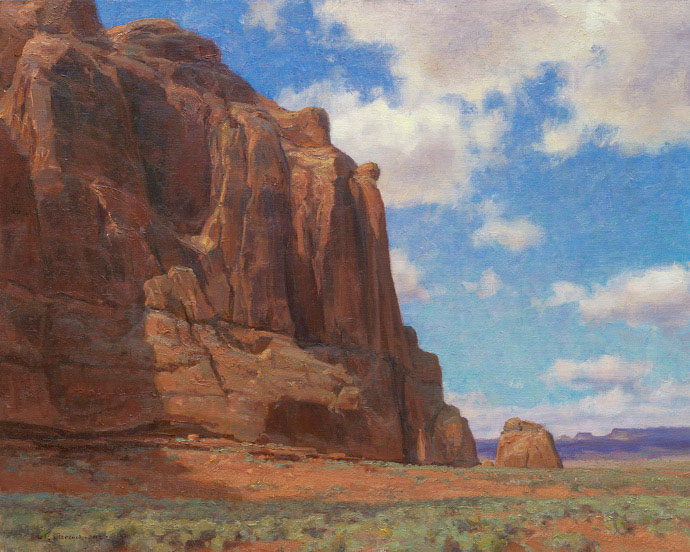

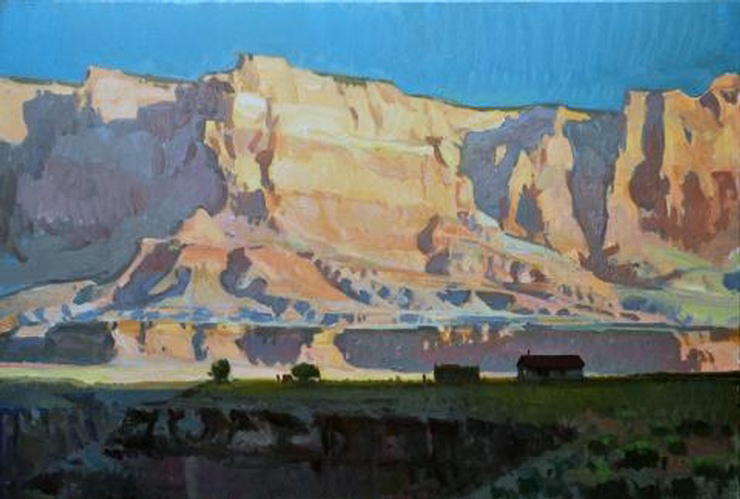

All of this said, there can be a primary center of interest, a secondary center of interest, or even a tertiary center of interest if one is stronger and others less so. An artist who can do this well is approaching mastery. In this painting by Josh Elliott, the left side of Shiprock is the primary center of interest and the buildings in the foreground are a secondary center of interest. Because the buildings are in shadow and read to the viewer as a part of the shadowed foreground, then they do not overwhelm the primary center of interest.

Josh Elliott - Unknown Title

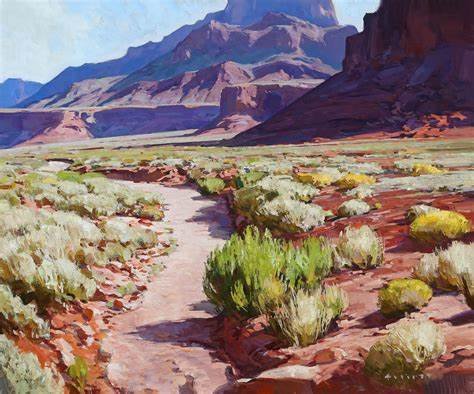

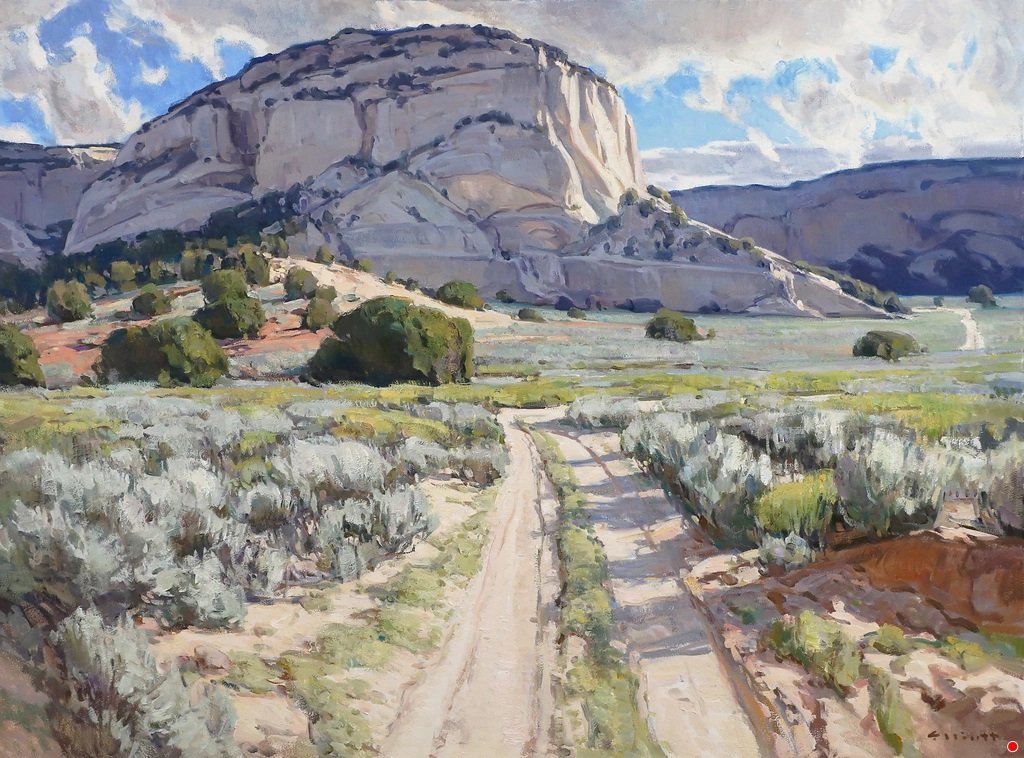

The other compositional element that works in conjunction with the center of interest is the eye path. The eye path is the way that the viewer’s eye moves into and through the painting. Is there a river, stream, arroyo, or pathway that draws your eye into the distance?

Josh Elliott - Unknown Title

Josh Elliott - Unknown Title

Do elements in the painting point from one thing to another moving towards the horizon line and the sky?

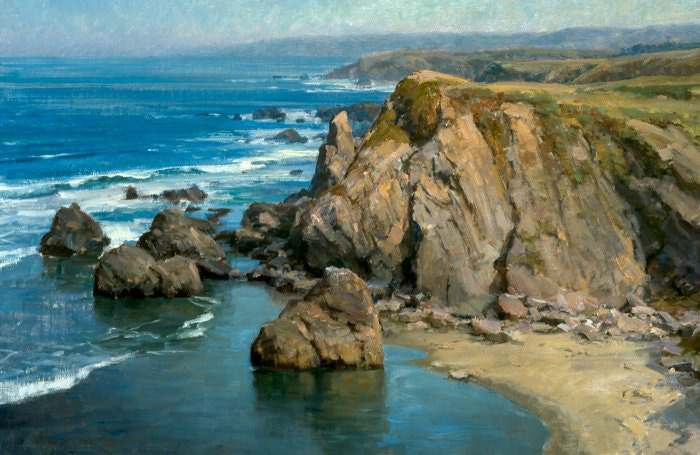

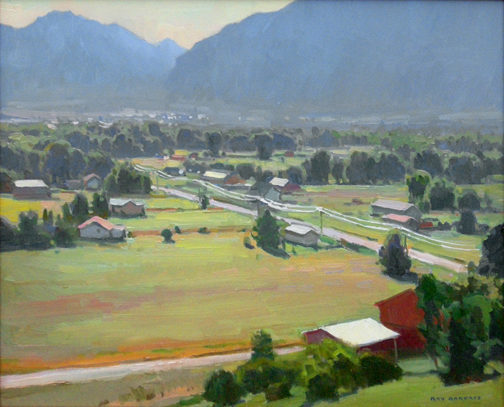

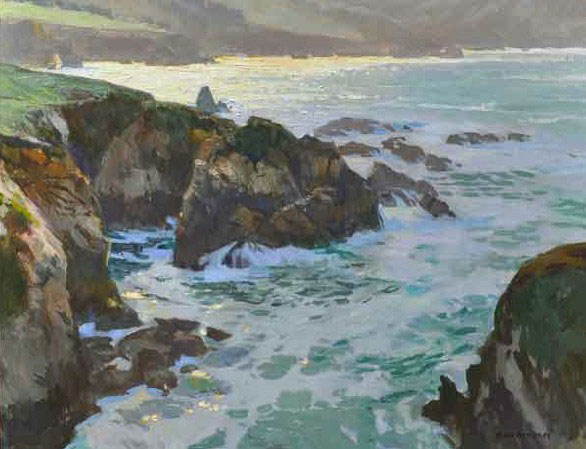

Ray Roberts - Unknown Title

Observe how the foreground rocks and water in the above painting by Ray Roberts lead the eye towards the distant cliffs and horizon line.

James Reynolds - Unknown Title

The shoreline in this painting by James Reynolds leads the eye to the bushes and small stand of pines on the right, then upward to the left through the light green patch to the large stand of pine and snowy peak just left of the middle of the painting.

I believe that composition in landscape painting is more difficult to manage than in any of the other representational genres.

REASON 2: MASSING

Massing is choosing where in a painting to add detail and where to leave it out or “mass” the elements together.

I have seen many paintings in which the artist is a good drafter and adds significant detail to the foreground, the middle ground, and the background. While this is technically impressive, it is nonetheless hard to look at. An artist should show the viewer what is most important to look at in the painting, and massing is one of the ways to do this.

I believe that the tendency to add detail everywhere comes from the ubiquity of photography in our lives. In general, most photos are full of detail everywhere, but the human eye does not really see the world the way a camera does. Our eyes see a central object or area that we are focusing on, and our peripheral vision is not as sharp. Good painting imitates human vision more than it does photography. This is not to say that the peripheral parts of a painting should be a blur, but rather that they should be subordinate to the center of interest and factored into the eye path of the painting.

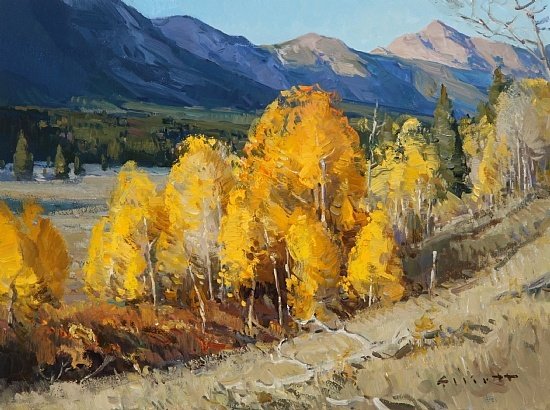

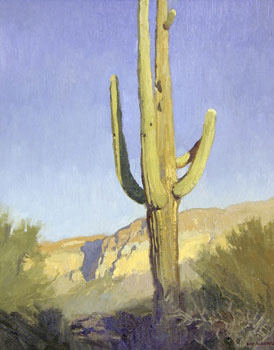

In landscape painting, this often means that each leaf or blade of grass in a painting should not be individually painted, but instead, that the tree should be one large shape with perhaps some leaves painted in relative detail in strategic places to suggest the presence of leaves throughout.

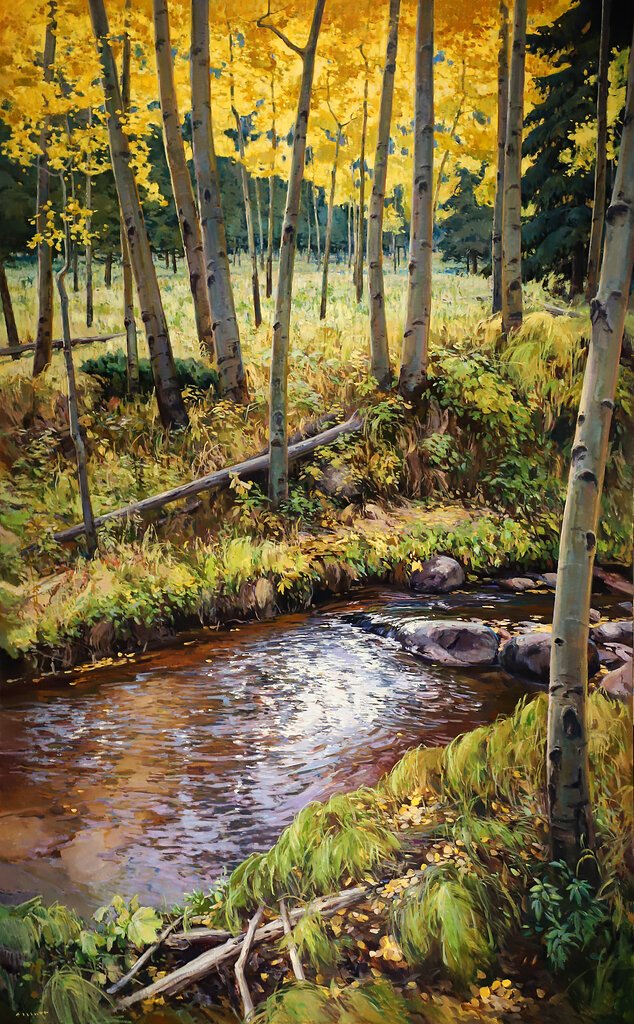

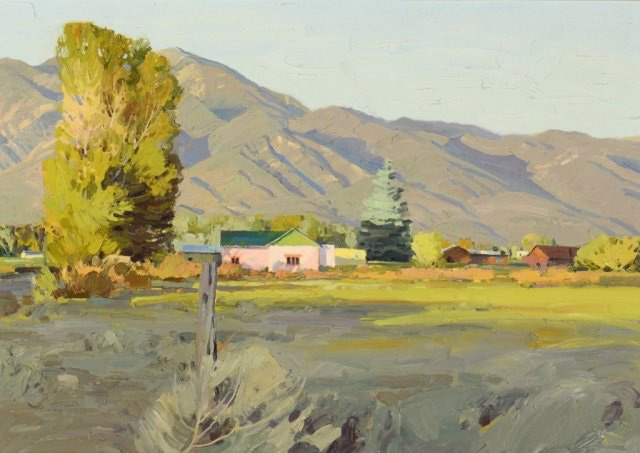

Josh Elliott - Unknown Title

Ray Roberts - Unknown Title

The concept of massing (versus detail) is akin to what in the world of biology is called lumping versus splitting. In my study of malacology (shells), I learned that some malacologists have the tendency to want to make broad definitions that cover large numbers of species of mollusks (shells) and some malacologists want to make many small categories whenever slight differences occur. Each approach has its pit falls. Lumping will ultimately end up with such broad categories that those categories become unwieldy, with items placed in them being significantly different from each other. On the other hand, splitting will generate so many categories that there may be no real significant differences between the categories.

This concept also applies to other disciplines like literature, history and music, in which categories are carefully defined and applied. Some individuals tend towards fewer broad categories and some individuals tend towards many smaller categories.

Of course, this concept also applies to categories in art history. Was this painter an impressionist or not? Or do we want to make a new category called the “luminists”?

The way that I apply the concept of lumping versus splitting is somewhat different, however. In representational painting it is the choice between what details to put into a painting (detailing or splitting up an element) and where to do this, and what details to leave out of the painting (massing or lumping elements in the painting) and where to do this.

I believe that the distinction between massing and detailing is the single most difficult balance to master when painting in any representational genre, and especially when painting the landscape.

And so my thesis is that understanding and applying massing is harder than any other component of representational painting. It is harder than composition, values (although they are a close second), color, temperature, drafting, edges, brushwork, or anything else.

As I have watched the careers of many painters over decades, I have observed that most good painters started at one time by putting in way too many details and have learned to mass over time. There are smaller numbers who start with too little detail and then learn to add additional detail to the right places as they grow as painters.

This last tenancy (to add too few details or to under paint) describes the difference between illustration and fine art, something that Roy Anderson taught me in his book, Dream Spinner: the Art of Roy Andersen. In his book, Andersen explains that illustration is meant to have short term function while fine art is meant to have long term function. While illustration is glanced at briefly, a painting will hang in a home for years and must have enough to keep the viewer engaged long-term. And that “enough” is not excessive detail, but rather compositional orchestration, good values, color, temperature, drafting, edges, brushwork, etc.

REASON 3: ARRANGEMENT OF ELEMENTS

I credit Clyde Aspevig with teaching me this concept, and at the time it seemed like the most foreign thing in the world.

Years ago, I went to a presentation given by Clyde Aspevig sponsored by the Scottsdale Artists’ School and he talked about many painting ideas, among them purposefully moving and altering elements in the landscape. Aspevig told us that early in his career he looked for the perfect landscape, but he never found one. At some point, he realized that as an artist, he could rearrange the elements of the landscape to be more interesting and closer to perfection.

For example, if you have a line of trees that are all the same size and height, the painter might change them to make some taller and larger and some smaller and shorter.

Clyde Aspevig - Unknown Title

This concept was further strengthened for me when an art mentor taught me the phrase, “No two intervals (or elements) the same.” As applied to the above example, then not only should no two trees be the same in size or height, but they should also not be the same distance apart.

John F. Carlson said, “Never take nature as stupidly as you find it.”

The best landscape painters will adjust the elements in the landscape to be more interesting to the viewer and make sure that no two trees, rocks, mountains, etc. look the same.

Clyde Aspevig - Unknown Title

CONCLUSION

When you factor in composition, massing and movement of elements in painting the landscape, then you begin to see that landscape painting is significantly more challenging than you would guess.

As an example, I have a dear friend who is an accomplished painter of portraits, figures, and animals. She once agreed to paint a small landscape for a show of landscape works that curated. She did a good job, but told me that it was a struggle, even though she often painted background landscapes into her figurative works. The orchestration of the painting was significantly different than anything she had ever done before. Her final comment was, “Landscapes are hard!”