The 11th annual Scottsdale Art Auction was recently held (http://scottsdaleartauction.com), and the Thursday night before the auction, I had the privilege of spending an evening looking at all of the auction items on the second floor of the Legacy Gallery in downtown Scottsdale. It is truly better art than you will find together in one place almost anywhere, including in most museums. This year was no exception, with outstanding art by a wide range of mostly deceased Western artists. A notable exception to that is the art of Howard Terpning. Howard is still alive, and his art is incredible to see in person. And as you know if you know much at all about Western art, his works sell for truly remarkable prices for a living artist. This year the selection of his paintings were not his best, but they sold for around $250,000 each.

The reason that I believe that Howard Terpning is so great is that he has no weaknesses. Nearly all of the top painters today, although usually very accomplished in almost everything, generally have a weakness. It might be color, drafting, composition, brush work, massing, edges, or values, to name the major categories. Howard is strong in every single one of these areas, and because of his technical excellence, his passion for his subject shines through. "How does he do it?" I wondered as I looked at his paintings in the art auction show. This is something that I have wondered for quite some time.

At about this same time, I ordered a book on the Taos Painters from an online vendor. When it came, it was the wrong book. Dang! I hate it when that happens! Do I want the hassle of trying to return it, or should I just reorder the book I really wanted in the first place? The book that came in the mail turned out to be Masters of Western Art written by Mary Carroll Nelson and published in 1982. After flipping through the book, I decided to keep it. One of the major reasons was that it contained a section on Howard Terpning written when he had only been painting full time for about 5 years. (Prior to that time, he was a successful illustrator.)

I read through the 10 pages contained in the book about Howard, and while the biography and photo of his studio were good, what really interested me was the 4-page demonstration of his working method.

Rough Sketch: Howard begins with a rough sketch to establish composition and values:

Preliminary Drawing: Then Howard does a preliminary drawing which is later transferred to the canvas before he begins to paint. In this preliminary drawing, he essentially does more work on the center on interest (the party of Indians) and further developes the foreground.

Preparing the Canvas: Next, Howard tones the canvas and transfers the preliminary drawing to it using light gray chalk. Look at the bottom right-hand corner of the image below and you will see a section showing this under-painting with some gray-chalk outlines which are barely discernible.

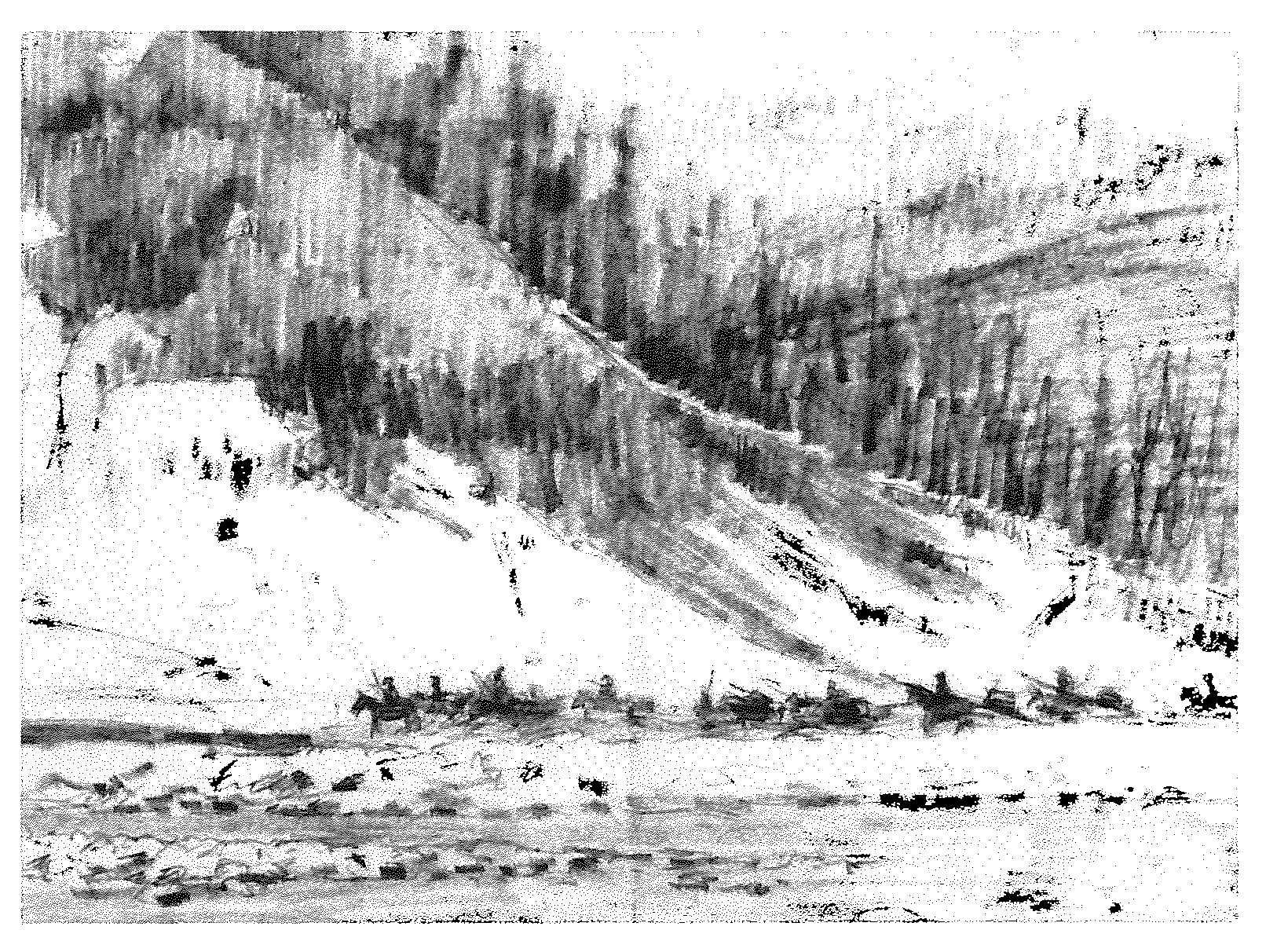

Blocking In: He follows up the the toning of the canvas by blocking in all of the major sections of the painting with thin paint applied in large brush strokes. This more fully establishes the value relationships and adds a gestural dynamic to the painting:

Developing Large Shapes and Colors: The next stage consists of further development of the large shapes and colors. Notice how he very carefully preserves his original value relationships. The painting is still fairly loose at this point and the large masses are readily apparent.

Center of Interest: In the next phase, Howard works on the center of interest, the figures and the horses, keeping the values simple and the anatomy correct. The center of interest should be somewhat more developed than the surrounding landscape, but not be over painted.

Development of the Surrounding Landscape: At this point, Howard works on the sky, the cliff, the pine trees and the distant mountains. Again, the idea is to make everything appear structurally correct without overworking anything.

Finishing Up: Lastly, Howard finishes the horses and figures. The farther they recede into the paining, the more monochromatic and simple they become. He finishes the water and the foreground rocks, not painting individual rocks, but suggesting their shapes.

Moving Day on the Flathead, by Howard Terpning, 1981, 40" x 58". Winner of the Prix de West in 1981, permanent collection of the National Cowboy Hall of Fame.

(I apologize for the line on the photo. The finished painting was spread over 2 pages in the book, and this was the best that I could do.)

Part of perfectionism is to know yourself well enough to have a work flow process that anticipates and forestalls errors such as drafting problems, edge problems, loss of value relationships, overworking, etc. I would love to ask Howard if, after another 30 years of painting, he still uses this same working method. My guess is that he does. Having the discipline to do a rough sketch, preliminary drawing, tone the canvas, block in, etc. seems tedious, but the truth is that it is the fastest and most reliable way to a great product in the shortest amount of time. If you have ever started a painting and then lost your way or had to throw it out because you couldn't solve the problems, then you will understand.